Thanks to powerful search features that have been developed in recent years, you no longer need to manually browse your computer’s hard drive if you’re looking for a file. Instead, you let the machine’s search technology find the file for you.

As another advancement in this field, Apple introduced a novel UI element in OS X 10.7 Lion: The so called “search token” aims to simplify compound searches.

Entering compound file searches

A compound search combines searches across several metadata fields to fine-tune the list of resulting matches.

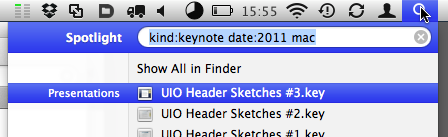

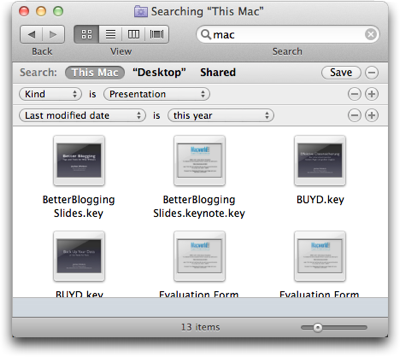

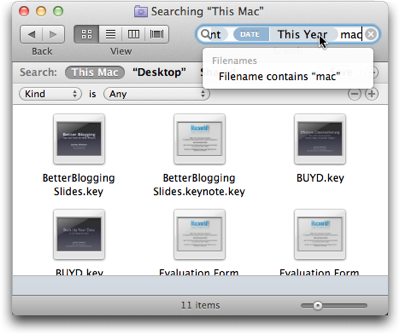

For example, to find all presentations about Mac topics from this year1, you might look for files whose …

- kind is (Keynote) presentation,

- date is this year, and

- contents include “Mac”.

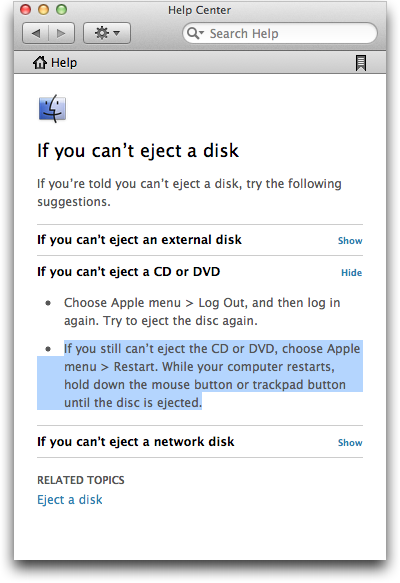

Previous versions of Mac OS X offered two methods for entering this kind of search. The more efficient one uses Spotlight with search operators like “kind:” or “date:”.

To run the example search, you would enter “kind:pdf date:2011 mac”2 into Spotlight’s search field.

Apple has published a complete list of Spotlight operators as well as further information on how to use Spotlight operators on their support website.

Besides having to remember which operators are available, and what their correct spelling is, you must know about this Spotlight feature in the first place. The chance of accidentally discovering it is very slim.

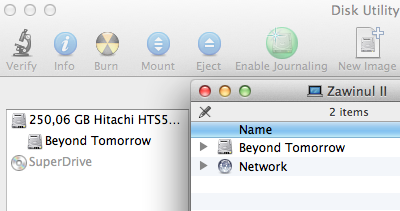

The second method for entering a compound search is by using the metadata fields in the Finder’s search window.

While entering a search this way is not as efficient as using Spotlight operators, it is much easier to discover, and the menus provide a built-in reference for the searchable file attributes.

The best of both of these methods has been combined into the new “search tokens”: Pure text entry and a menu of search suggestions.

Entering compound file searches with tokens

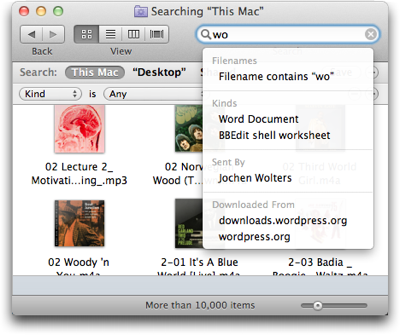

As soon as you start typing something into a Finder window’s search field, a menu pops up. Its contents are grouped by the metadata fields in which your search string was found.

When you see what you’re looking for, you select its menu item with a mouse click or via the cursor keys on your keyboard. There is no need to switch between keyboard and mouse while you refine your search.

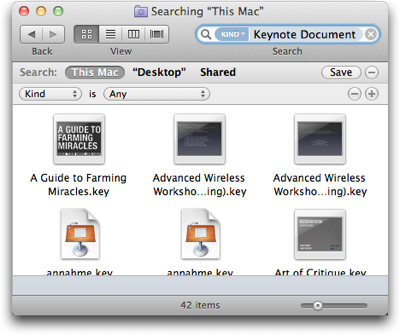

When you make a selection from the menu, the search is encapsulated in a lozenge-shaped token, which combines your search term with the metadata field within which the search is performed.

After adding a new token, you can continue typing to further refine your search.

Unfortunately, the search field has a maximum width of about 35 characters, regardless of how you configure the toolbar in the Finder windows.

On average, this should be sufficient room for two or three search tokens. If you enter a more complex search, however, you cannot see the entire set of criteria at a single glance anymore.3

Combining the best of both worlds — and adding a caveat

Entering compound searches with the new search tokens merges the efficiency of typing into a text field with the discoverability of a menu.

Thanks to the tokens, you need to type even less than if you used Spotlight operators. That’s because you only need to enter the search terms, but not the operators themselves, as you pick these from the menu.

Besides the limited space in the search field, the current implementation of search tokens has one caveat: They only support a small subset of all available file metadata fields. Many more are available in the search section underneath the Finder windows’ toolbar.

Despite these shortcomings, the search tokens make performing compound searches of medium complexity more convenient and more efficient than either of the older methods.

-

This article was written in 2011. Therefore, even though it was published in early 2012, it refers to “this year” as being 2011. ↩

-

According to Apple’s documentation, “date:this year” is supported as well, but I couldn’t get it to work on my machine. Hence the hard-coded “2011”. ↩

-

There is a workaround, but it’s rather tedious: If you save a search and then select Show Search Criteria from the resulting Smart Folder’s context menu, the search criteria will not be shown as tokens anymore, but appear in the search fields underneath the toolbar. ↩