Mobile Safari currently supports three search engines, Google, Yahoo!, and Bing. All three of these present their search results on web pages that have been optimized for viewing on mobile devices. Also, all three can show search results on a map. The are differences in how easy these maps can be navigated, however.

For testing, I used the search term “market street san francisco,” which has two interesting characteristics: first, the search engines should easily recognize this as a geographical location, namely Market Street in SF; and second, there is a good chance of also finding businesses that refer to Market Street in their name, or that are simply located along that road.

Here’s what I — quite literally — found.1

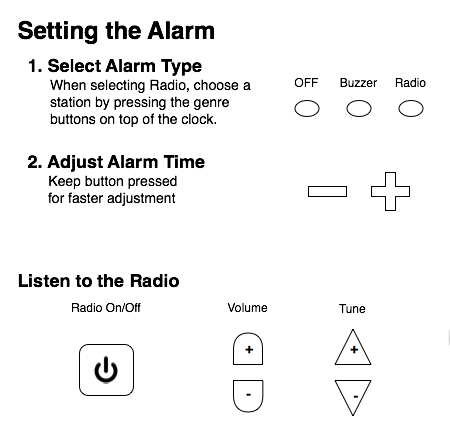

Discovering the map: A map preview appears directly on the search results page. It’s just below the fold on an iPhone and shows a number of location markers.

The frame around the map has the same color as standard Google text links, indicating that the map itself is tappable.

Navigating the map: You move the map around via tap-and-drag. Double-tapping zooms into the map by a fixed ratio, and the pinching/spreading gestures zoom out of, and into, the map, respectively.

While these interactions may be difficult to discover because they are invisible, they do follow the standards defined by the Photos and Maps apps.

Finding search results on the map: Information about the locations that are marked, appears below the map.

If there are multiple search results, you can step through them with left/right buttons. When you do so, the map is automatically re-centered around the selected result. This also works the other way ’round: tap a location marker, and the information below the map will change to the corresponding location. All of this works without the map page being reloaded.

One detail I miss is a dedicated “Re-center” button to get back to your marked location in case you moved the map so far that the marker ended up off-screen. As a workaround for a search with multiple results, you can step to the next result, and then right back to the previous one, to find that location again. This won’t work for single search results, however, as you can see here:

Noteworthy details: The two buttons in the top corners of the map open the currently selected location in the “Search” and “Directions” views in Maps, respectively. In the case of “Directions,” the location is entered into the “End:” field for quickly looking up the route to get there.

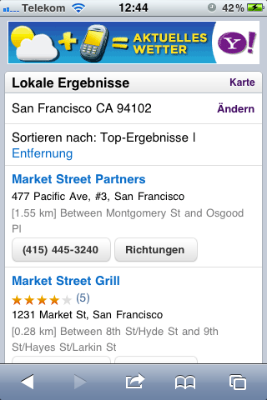

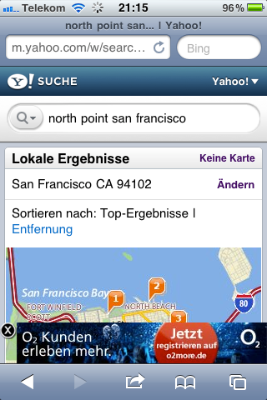

Yahoo!

Discovering the map: The search results on Yahoo! include “local results” (“Lokale Ergebnisse”), but these are not displayed on a map (pre)view. To show the results on a map, you have to click a “Map” (“Karte”) link in the “local result” section’s header.

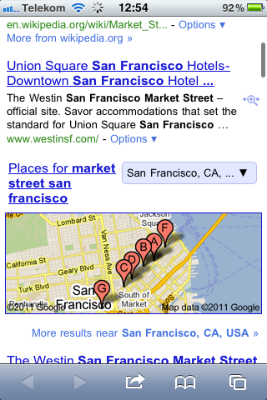

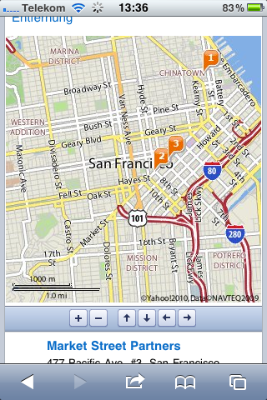

Navigating the map: Yahoo! uses static images for the map, and displays it on a scrollable page.

To zoom in or out, or to move it, you have to tap on one of six buttons shown below the map. The only gesture you can use on the map is double-tapping, which will vertically center the map on the screen.

The map’s navigation buttons are tiny. Although there is ample horizontal room on that button bar, the designer chose square buttons over wider, rectangular ones that would be easier to hit. There is hardly any room between the buttons, either.

The page is reloaded every time you move or zoom the map. Unfortunately, the vertical scroll position of the page may shift slightly between reloads. E.g., when I tapped the down arrow on this screen…

… the map’s position moved slightly upwards after loading the new map image:

Finding search results on the map: The list of search results is displayed below the map. Markers on the map show their corresponding locations.

There are no links between the two, though, so you have to manually correlate the list items with their respective location markers.

The page lists up to ten search results at a time. On the small screen of an iPhone or iPod touch, this means you will likely need to scroll back and forth quite often to fully grasp which map location belongs to which description.

Noteworthy details: Sometimes, Yahoo! will display ads as overlays at the bottom of the map page. These hide automatically while you are scrolling, but still feel more intrusive than the ones that Google sometimes displays right on the map.

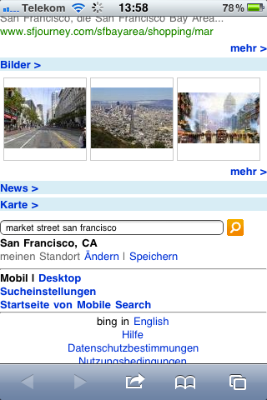

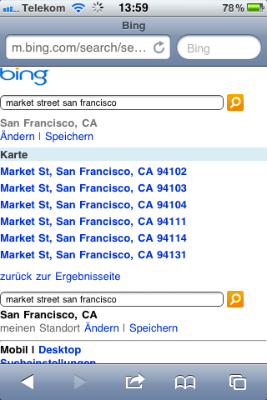

Bing

Discovering the map: Bing displayed the shortest results list by far, with only two webpage links and three images. A map may also show up on the results page, unless the location it found extends over multiple ZIP code regions.

In that case, you only see a “Map” (“Karte”) text link, which takes you to a list of ZIP codes.

Imagine being in an unfamiliar city and running a web search similar to “market street san francisco.” Would you feel comfortable picking a neighborhood of that city to limit your search on, based only on a ZIP code?

I think that filtering a geographical search should happen via selecting a region in a map view, but not before you have even seen that map for the first time.

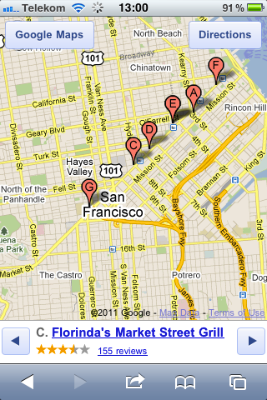

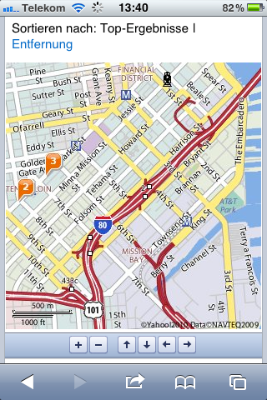

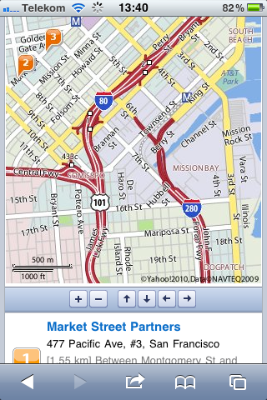

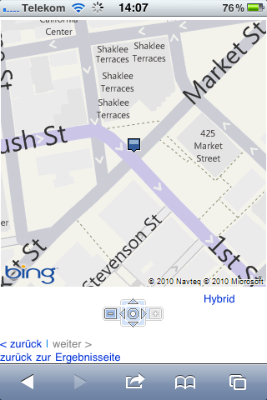

Navigating the map: The way in which Bing displays the map is similar to Yahoo!’s: the map itself is a static image on a scrollable page, buttons are used for zooming and moving the map, and (single-)tapping the map image centers the page.

It reloads the page to update the map image, and it also shares the flaw of not preserving the vertical scroll position between such reloads.

The buttons below the Bing map are even smaller than Yahoo!’s, and are placed even closer together. The location of the zoom buttons — one each to the left and right of the “cursor” buttons — is unfortunate, because it breaks up proper grouping of the controls for zooming and navigation. (Yahoo! gets this right.)

I do like the arrangement of the navigation buttons in a compass dial for its natural mapping. This one even features a “re-center around location marker” button at its center, whose functionality neither Google nor Yahoo! offer.

What I don’t understand is why the entire assembly isn’t at least twice as big. As you can see in the following screenshot, the reason for this design is not a lack of available space.

Finding search results on the map: Interestingly, Bing comes up with much fewer search results overall. For “market street san francisco,” it only found the actual street, but none of the results — retail stores, hotels, etc. — that Google or Yahoo! found.

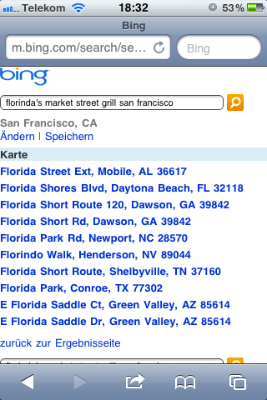

Some searches found a single correct match each, while other perfectly reasonable search terms like “apple store san francisco” or “cha am restaurant san francisco” came up empty. Yet other searches like “florinda’s market street grill san francisco” (as found by Google earlier) made Bing deliver “matches” that are surprisingly out of line:

Noteworthy details: The results page itself is somewhat zoomable, i.e., its width is not fixed to that of the screen. When I first tried the spread gesture on the Bing map, I initially thought I could zoom the actual map this way, until I realized that I had zoomed the entire page.

Show me the way, Google!

In general, using buttons for zooming and moving a map might work almost just as well as direct manipulation — albeit with a much smaller dose of “touch-screen magic.” The way that this approach has been implemented by Yahoo! and Bing, however, is plagued by a number of flaws.

The buttons are too small, their spacing is too narrow, reloading the page for every zoom or move operation feels disruptive, and manually correlating location markers with particular search results is tedious.

Google’s direct-manipulation map is not only more intuitive and more convenient to use. It also makes great use of the available screen real-estate, displaying all related data in a single screen-full that does not require any scrolling.

Being able to move and zoom the map without reloading the page gives you a great sense of direction: you can easily see where you are “going” while dragging the map’s contents around.

In short, despite being “optimized for mobile,” Bing’s and Yahoo!’s map web pages still feel like, well, web pages. In comparison, Google’s map feels like a veritable application: if it weren’t for the browser chrome, you might think that it’s a native iOS app.

-

I was in Germany while testing this, so the look as well as the contents of the search results may differ from what you get in your own locale. ↩