Error messages are always annoying, but designers and developers can make them less painful by addressing three questions (in a language that is meaningful to their users):

- What went wrong?

- Why did it go wrong?

- What can the user do to fix it?

This applies to all error messages, regardless of the context in which they appear. Case in point: Messages that mail servers add when they reject — or “bounce” — an email.

Feels like email support purgatory

When I tried to send a command to an email list server a few months ago, the email was rejected with this error message:

SMTP error from remote mail server after initial connection:

host [REDACTED]: 554 [REDACTED] ESMTP not accepting messagesThe message text makes it sound as if this server is not accepting any messages. But then there’s the 554 error code, which is commonly used when a server rejects an email which it considers to be spam.

To fix the problem, I contacted the help desk at the university that hosts this list server, using their publicly accessible website.

They responded via email, saying that they had assigned and update the support ticket, and included a link to the ticket on their website. After clicking the link, I was asked to sign into the university website — which I couldn’t do, since I was not a student there and, thus, had no account for the site.

My direct email response bounced as well, so I had to open another ticket to follow up with them. In response to which I received another update email with the same kind of useless-to-me link. So I submitted yet another support ticket, explaining to them the original problem; that my direct responses to them bounced too; and that I could not sign into their support website, either.

Although they had already received complete headers from my original email and from the bounced response to their help desk’s email, their next response said:

Please attach or copy/paste the original message to the ticket so we can review of [sic] troubleshooting purposes.

Picture me, sitting in front of my computer, a desperate look on my face, flailing my arms wildly, and screaming, “BUT HOW?!”

So I simply gave up.

My original email just wasn’t important enough that I would endure this nonsense any longer.

A clear and simple path towards un-blocking your emails

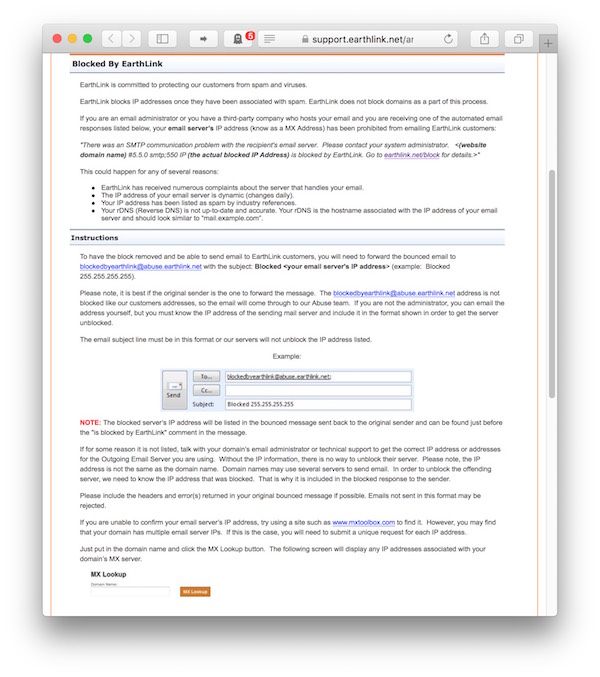

A more meaningful error message for the exact same condition (namely that the receiving server intentionally rejects an incoming message) is this one from EarthLink:

SMTP error from remote mail server after MAIL FROM:[REDACTED] SIZE=2379:

host [REDACTED]: 550 IP [REDACTED] is blocked by EarthLink.

Go to earthlink.net/block for details.It clearly explains the issue, and does so in a language that does not require in-depth IT knowledge to understand. More importantly, the page that the included link points to answers the three key questions listed earlier:

- What went wrong,

- why it went wrong, and

- what you can do to fix it.

While it was still a bit of a hassle to have our server removed from EarthLink’s black list, the error message and the support page provide enough information to understand what to do next.

An essential component of this process is that the admins at EarthLink provide an email address — blockedbyearthlink@abuse.earthlink.net — that does not block any incoming messages. It’s this detail that makes direct email communication with the support team possible, so that the workflow is much more convenient and efficient than what the above university had to offer.

Addressing rejected emails the Google way (and it ain’t pretty)

Alas, sometimes even a meaningful error message and a link to further information still doesn’t suffice.

For reasons unbeknownst to me, Google has been considering me a spammer for the last couple of months. Emails to Gmail accounts regularly end up in the recipients’ spam folder, even though the messages’ contents don’t feel at all “spammy” to me. We also never found evidence (in the log files, etc.) of spam emails being sent from the root server that we share with some friends.

This problem has gotten to the point where Gmail has rejected my emails outright. The error message that was contained in the responses is very well-phrased, and it also contains a link to further information.

Delivery to the following recipient failed permanently:

[redacted]

Technical details of permanent failure:

Message rejected by Google Groups. Please visit

http://mail.google.com/support/answer/188131?hl=en

to review our Bulk Email Senders Guidelines.This does not make sense, though: The messages were sent to individual Gmail accounts, not to Google Groups, and they did not originate from an account that would even remotely qualify as a “Bulk Email Sender,” either.

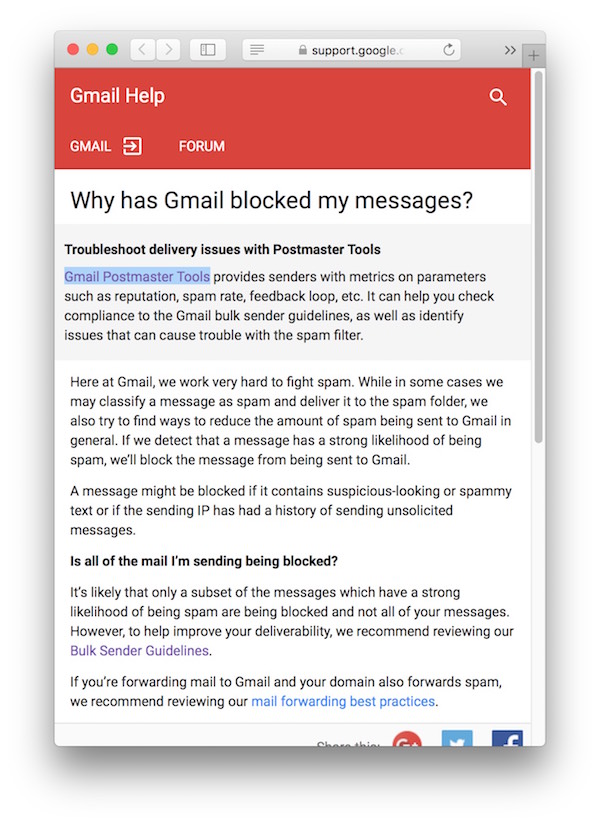

Following the link to their support page provides an “outstanding” example for what I think is the biggest flaw in Google’s overall philosophy.

For Google, there is a solution to every problem — but it is always a technological one.

If you have any problems with a Google product as a regular user, you can’t simply call a human at a support hotline. Instead, you’re referred to a support forum, which is often maintained by other users (but no official Google representatives), or you’re offered another tool to help you fix the problem you have with the first tool.

Same here: The help page explains perfectly well what happened, and why it might have happened. But the question “what do I do now?” is “answered” by pointing to the Gmail Postmaster Tools.

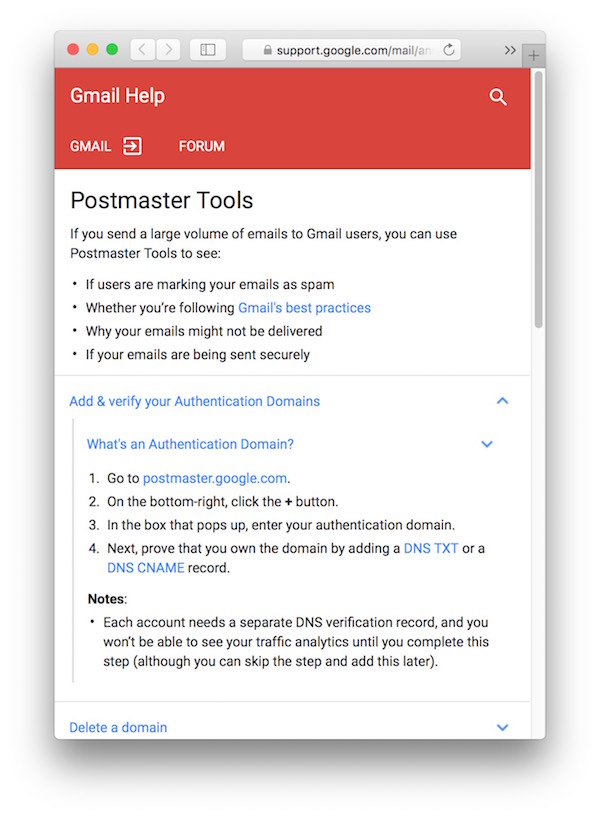

The help page for these Postmaster Tools states that this is for you, “[i]f you send a large volume of emails to Gmail users.” What, then, if it’s been only a handful of emails that were rejected, as in my case?

What’s more, the Postmaster Tools can only be used if you have your own domain. So what do you do if you use another large email provider like, say, Yahoo! or Hotmail, without your own domain?

Considering how many companies are using Gmail as their sole email service, not being able to reach these companies, because Gmail blocks your emails for some obscure reason, is not just annoying, but actually a bit scary.

Not having any way to easily fix any blocking, though, is just unforgivable, especially when we’re talking about a modern-day IT giant with a resource pool like Google’s.

Two of my rejected emails were job applications. I don’t know what, specifically, was wrong with them. But I do know that I have no alternative communication route into these companies, short of stalking their employees online. All because Google does not let me contact a human support person to help me solve this.

And people ask me why I am so critical of Google sometimes.