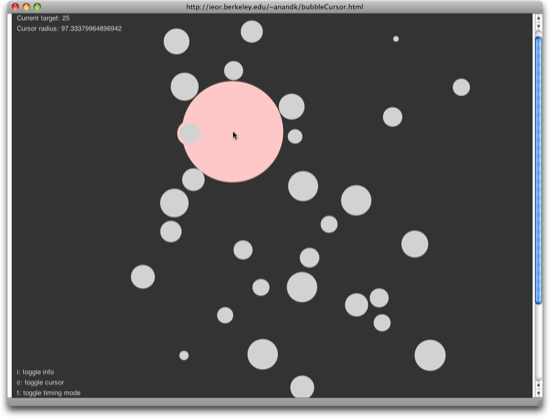

Anand Kulkarni has developed an interesting and fun demo of the bubble cursor, a UI concept conceived by Tovi Grossman and Ravin Balakrishnan.

Standard mouse pointers usually have just a single-pixel “hot spot.” It is this single pixel’s position that determines which UI element receives the click when the user presses a mouse (or trackpad, etc.) button. Because of the hot spot’s tiny size, it requires precision to hit a specific target on screen, especially if the target is small, too.1

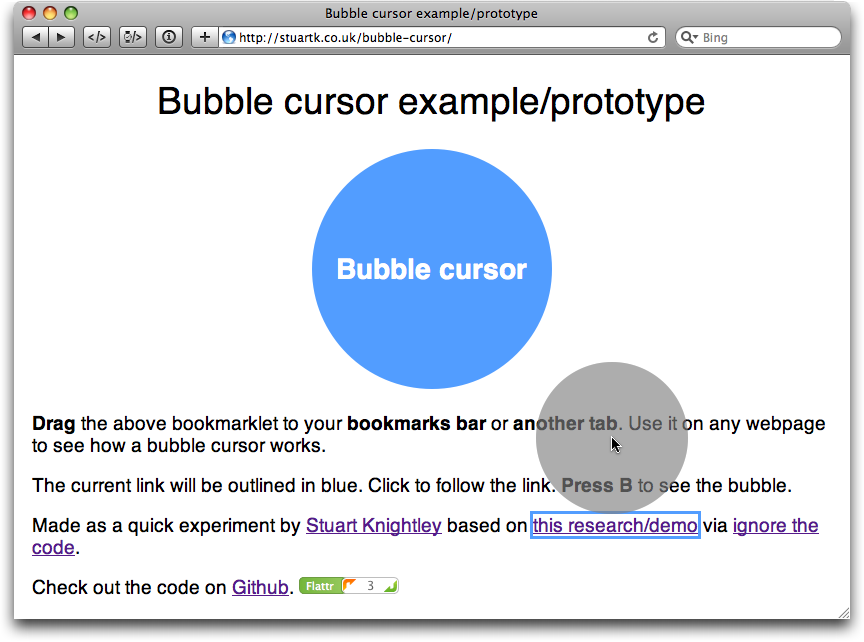

Grossman and Balakrishnan address this problem by expanding the cursor’s “hot spot” to a circular “hot area.” The area’s size dynamically adapts to the cursor’s position in relation to nearby UI widgets so that, at any given time, exactly one widget is selected as the click target.

Grossman’s and Balakrishnan’s 2005 CHI paper (1.1MB PDF) explains the idea in detail and contains research which shows that the bubble cursor is consistently more effective than single-pixel and fixed-size area cursors.

Thanks to Anand’s JavaScript-based demo, you can try out the bubble cursor hands-on.

Unfortunately, though, you cannot disable or modify the area indicator around the cursor. It would be interesting to see whether changing the area indicator influences the feel of using the bubble cursor and, if so, in what way. I’d especially like to try out the demo without any visual feedback except highlighting of the current click target.

Found via Nat Torkington’s Four short links: 23 September 2010

Update 2010-10-05: Stuart Knightley has implemented the bubble cursor as a JavaScript bookmarklet that works with just about any webpage, so you can test this interaction concept in a real-life setting. As an extra feature not included in Kulkarni’s demo, this bookmarklet lets you toggle the display of the cursor’s click area.

-

That’s Fitt’s Law at work again, of course. ↩