Last month, my wife and I attended the O’Reilly Design Conference in San Francisco. The conference offered great keynotes and presentations, and the venue — Fort Mason Center — was spectacular.

O’Reilly has compiled a list of the event’s keynote videos and speaker slides. Some slide decks can be downloaded directly from that page, while others are hosted on Speaker Deck or SlideShare. The workflows for downloading the decks from the latter two sites create surprisingly different user experiences.

Speaker Deck: “Click. Done!”

On Speaker Deck, the prominent “Share” section contains a Download PDF button. Click that button, and the PDF file instantly opens in the browser, from where you can easily save it to your computer. Alternatively, you can right-click on the Download button and directly download the file via the context menu.

Clean, quick, easy. Nice!

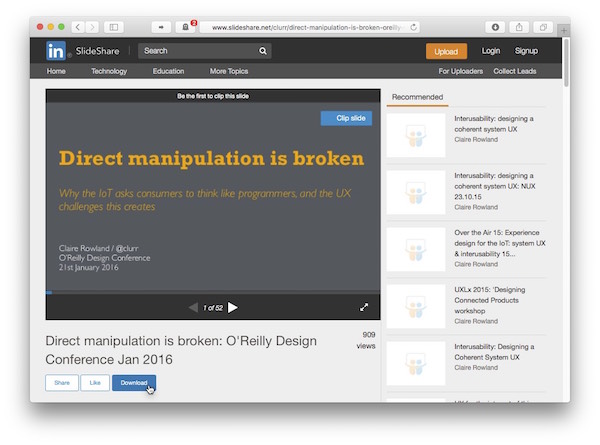

SlideShare: “No account? Not signed-in? No PDF!”

SlideShare’s Download button is just as easy to find.

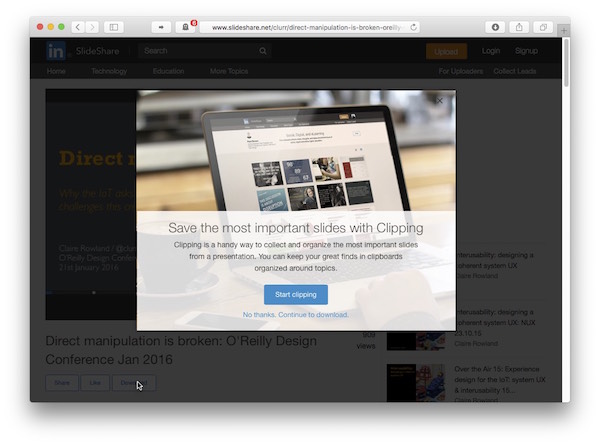

Click it, though, and instead of just starting the download, you see a dialog box about “Clippings.” At this point, I was just trying to download the file, so I chose to “[c]ontinue to [the] download.”

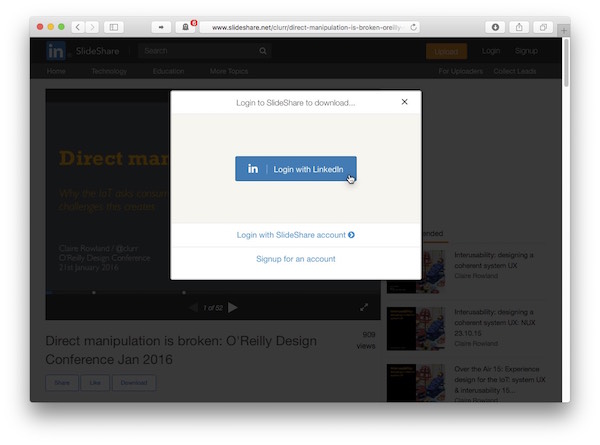

Clicking the link underneath the button does start the download — if, that is, you are signed into SlideShare. If you aren’t, you are requested to log into the site.

That, of course, also means that if you don’t yet have an account for SlideShare, you have to sign up for the site before being able to download any of the slide decks. At least the triggered download will start automatically once you’ve completed the login procedure.

Cumbersome by design

You can often hear designers and users complain about LinkedIn’s user interface, and it is LinkedIn that owns SlideShare. This simple download workflow is a good example for a less-than-stellar design decision.

Note how the clippings dialog box does not have a “Don’t ask me again” checkbox. And indeed: every time you decide to download a slide deck, that process will be interrupted by having to make the decision fore or against clippings. Every single time.

Worse yet, even if you adopt that feature by clicking Start clipping, and clipping a flew slides “just to be sure,” the dialog box will still appear whenever you click Download. In other words, even when the dialog box has done its duty, it will still come back time and again.

Who controls the content that you own?

This odd behavior aside, there’s a deeper, more philosophical issue to think about here.

Websites like SlideShare or Speaker Deck don’t own their users’ works, they just host them.

What does it say about a company, then, that they require you to have an account with them before you can access hosted content that, say, a conference speaker has made available? Why did Speaker Deck decide to make this process as painless as possible, while SlideShare uses it to attract new users? What would SlideShare lose by allowing a direct download without requiring visitors to log in?

And finally, does a conference speaker’s choice of provider reflect back on that speaker, because this download process might be perceived as being part of the overall presentation experience?

That said, from this conference attendee’s point of view, the most desirable option for this workflow actually is finding a direct download link to the PDF files right on the conference website. It doesn’t get much more efficient and convenient than that.