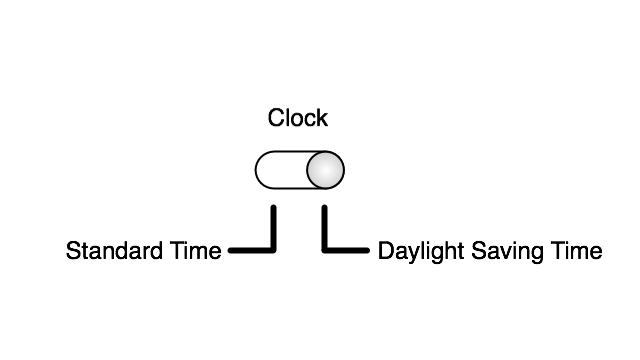

To most media company executives, Digital Rights Management is a means to prevent pirating of their digitally distributed content. Alas, what they rigorously keep ignoring is that the restrictions that come with DRM-“protected” content only affect honest customers, whereas pirates couldn’t care less.

Sometimes, DRM matters are made even worse by technical implementations that are plagued by major usability issues, resulting in an abysmal overall user experience.

A soulful case-in-point

Motown’s legendary studio band, The Funk Brothers, are among my all-time musical heroes. Their story is told in a wonderful documentary, entitled “Standing in the Shadows of Motown,” which has been published on DVD

a few years ago. As an enticing bonus, the DVD contains two Windows Media video files with the entire movie in HD format.

Sorry, Mac, you can’t play!

For a Mac user, the most common way of viewing video files is by opening them in QuickTime Player. While the QuickTime media architecture does not have built-in support for Windows Media files, you can make it “understand” Windows Media content by installing a software package called Flip4Mac.

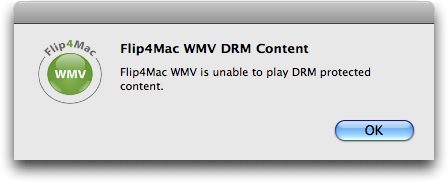

When I tried to open one of the two HD videos in QuickTime player, however, Flip4Mac brought up an error message, stating that it is “unable to play DRM protected content.”

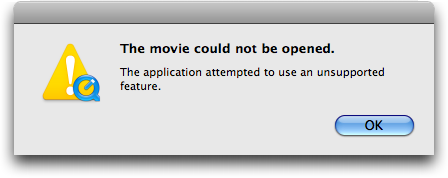

After I had dismissed the Flip4Mac error message, the QuickTime Player displayed another, which, due to the way it was phrased, added some confusion instead of helping me fix this problem.

Flip4Mac is the software officially endorsed by Microsoft for playing .wmv files under Mac OS X. Due to its lack of DRM support, though, the only way to view DRM-infested Windows Media content is on a machine running Microsoft Windows.

And even on that platform, some Windows Media files remain barred from — perfectly legal — access…

Software that’s old and tired

For those rare occasions when I need to test a website in Internet Explorer, I have a very clean and very up-to-date installation of Windows XP SP3, which I run under VMware Fusion on my Mac.

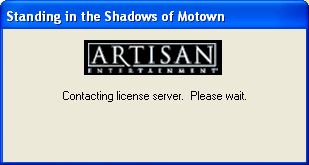

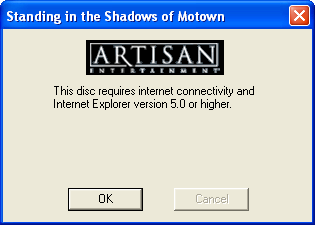

Assuming that I would be able to view the HD videos on this virtual machine, I launched WinXP in Fusion, opened the movie DVD in Windows Explorer, and double-clicked its dvdrun.exe file.

And up came this dialog box:

I wasn’t exactly sure which application this dialog box belonged to, but I did get my hopes up about being able to watch the movie files after all. Until…

Confirming that both of these requirements were met was as easy as launching Internet Explorer 8 and running an online search for “Artisan Entertainment.” One of the results was the Wikipedia entry for this company, which, incidentally, stated that they had been acquired by Lions Gate in 2003.

When an error message is factually wrong as in this case, this is not just a matter of bad design, what with the message being useless for finding a fix for the underlying issue. More often than not, it also means that said underlying issue is much worse than what it says in the error message.

Can I see your PC’s ID, please?

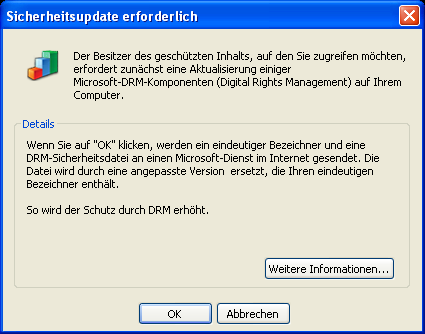

The one remaining option I could think of at this point was to open the movie files directly via double-clicking. As a result, Windows informed me about requiring some kind of update:

Security Update Required

The owner of the protected content which you wish to access requires an update to some Microsoft DRM components (Digital Rights Management) on your computer.

If you click “OK,” a unique identifier and a DRM security file will be sent to a Microsoft service on the Internet. The file will be replaced by an adapted version containing your unique identifier.

This way, the protection through DRM will be increased.

The “More Information” button leads to a page on the Microsoft website, stating the following:

Security Upgrade

Owners of secure content may also require you to upgrade some of the DRM components on your computer before accessing their content. When you attempt to play such content, Windows Media Player will notify you that a DRM Upgrade is required and then ask for your consent before the DRM Upgrade is downloaded (third party playback software may do the same). If you decline the upgrade, you will not be able to access content that requires the DRM Upgrade; however, you will still be able to access unprotected content and secure content that does not require the upgrade. If you accept the upgrade, Windows Media Player will connect to an Internet site operated by Microsoft and will send a unique identifier along with a Windows Media Player security file. This unique identifier does not contain any personal identifiable information. Microsoft will then replace the security file with a customized version of the file that contains your unique identifier. This increases the level of protection provided by DRM.

Note how this text slyly mentions “personal identifiable information” while leaving the user in the dark about what, exactly, the “unique identifier” contains. It neither explains what this identifier’s function is, nor how it “increases the level of protection.”

I’m not sure whether this is just bad technical writing, or whether this text is intentionally vague. In any case, the result of this phrasing is that, to a non-techie user, this request may sound like this: “Before we let you view this content, we’ll have to do something to your computer, but we don’t really want you to know what exactly that is. Just trust us!”

I also wonder whether this is a one-off process that will enable viewing other DRM-“protected” content on this computer in the future, or whether this process has to be followed for every single file or, at least, for every unique publisher/content provider.

A server detour to nowhere

Once the update process had completed, the Windows Media Player launched and started loading the movie file. Instead of simply playing the video, however, a window titled “License Acquisition” was opened:

Apparently, the “security update” did not suffice. I had to go through further licensing hoopla before accessing content that — just as a quick reminder — I had paid for.

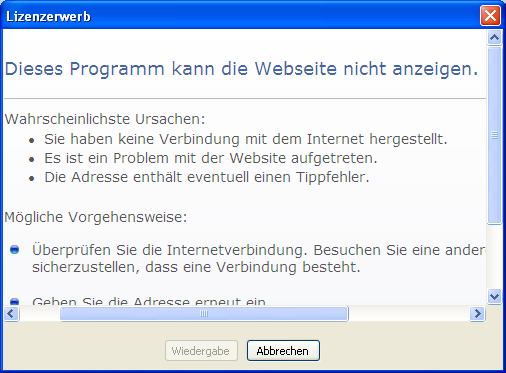

It didn’t take too long, and that black void in the window was filled — with a default webview error message:

What you see in this screenshot is the standard error message — “This program cannot display the webpage” — that an IE-based webview will display when it is unable to connect to a server.

This message along with its trouble-shooting tips is, of course, completely and utterly useless at this point, because it is out of context: I am not accessing this website in a browser, but in a native application. Consequently, there is no way I could, say, manually enter the webserver’s URL again. I don’t even know what that URL is.

The only thing I can do at this point is verify that my machine’s Internet connection is working properly. If it does and, therefore, is not the cause for this error, I’m simply stuck.

Considering how old the DVD is — some seven years, or so — I assume that Media Player cannot fetch the required licensing information because the licensing server simply does not exist anymore or that it has moved to another domain.

The proper way to handle this problem would have been to display a message, stating that the software “Cannot retrieve the digital license required for viewing this video. Please verify that your Internet connection works properly, and try again. [OK]”

In fact, why not add an extra dose of honesty to that message: “If the problem persists, you’re screwed, because you won’t be able to access digital content that you honestly paid for. Sucker!!”

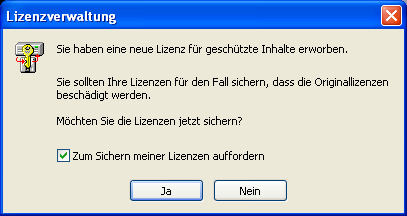

Adding insult to injury, I got to see this when I closed the Windows Media player application:

You have acquired a new license for protected content.

You should save your licenses in case the original licenses may be damaged.

Would you like to save the licenses now?

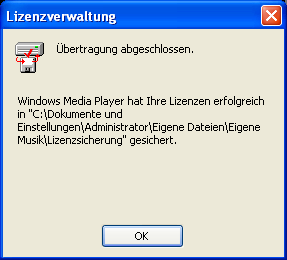

Clicking Yes is followed by a confirmation dialog, listing the path to the license file.

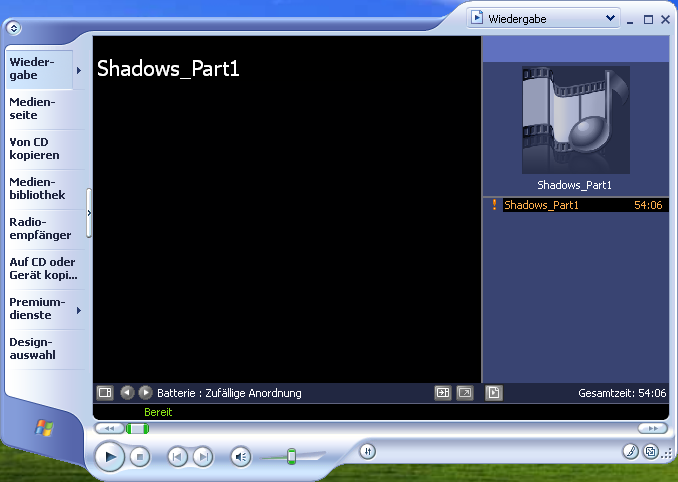

At the end of this annoying little DRM dance, Windows Media Player still added the movie file to its play list as if it were perfectly accessible.

Alas, it wouldn’t start playing, of course. And to nicely round off this awful experience, clicking the Media Player’s play button would start the whole process all over again.

DRM: As tiresome and offensive as it’s always been

Digital Rights Management technology not only puts limitations — and oftentimes severe limitations — on how honest customers can access digital media content they legally purchased. DRM can also be plagued by major usability problems, as seen in this case:

-

The software licensing check is not transparent: the user is confronted with additional windows with confusing wording that, from a non-technical user’s point of view, are not directly related to viewing the content.

-

“Unlocking” the content requires network access: if you try to initially access the content while you don’t have Internet access — on a plane, on a train, in a hotel, etc. — you’re out of luck. Also, you cannot tell from the information provided by Microsoft whether this update is required for each new content file you want to access, or whether a single update will suffice for accessing “protected” content in the future.

- Due to technical problems, the content may not be accessible at all, and there is no proper information why this is the case. If the licensor goes out of business, you may even lose access to their content for good.

It’s long overdue that media companies stop bossing their customers around once and for all: get rid of DRM technology and let your honest customers enjoy the media they purchased whenever, wherever, and however they want.

You know, just like pirates have been doing all along.